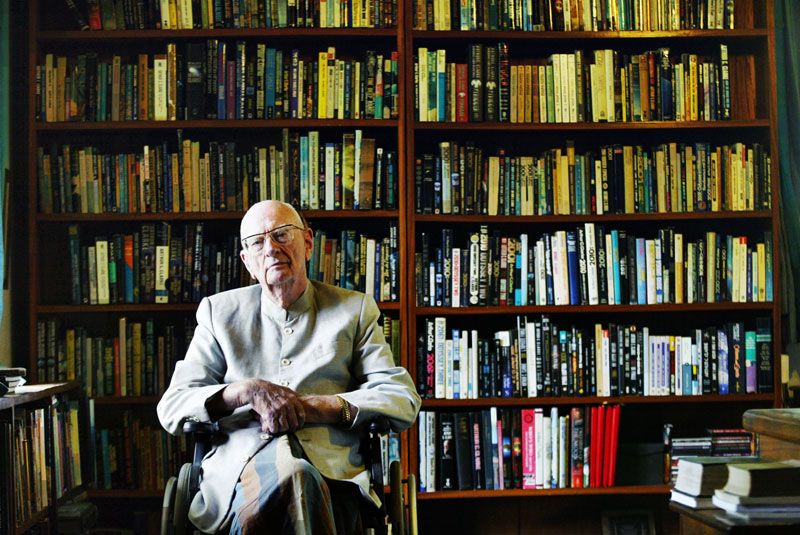

Today would have been Arthur C. Clarke's 96th birthday, not that the calendar or any other excuse is needed to celebrate his life and achievements.

In the five-and-a-half years since he died, Clarke's achievements seem to me only to have grown. Looking back now, four years shy of his centenary. I'm beginning to get a real sense of just how large that achievement is. And this after a lifetime of reading him (and even knowing him, a little, during the years I edited OMNI). Not many writers' accomplishments actually seem to enlarge after their death. Arthur Clarke's do, at least to me.

I think I was eight or nine the first time I read one of his novels — A Fall of Moondust in a Reader's DigestCondensed Books version. (I think that was the one and only time pure SF was tried by the company.)

It didn't take long for me to seek out — and, happily, find — more by him. In pretty quick order I worked my way through the first round of classic Clarke:

Earthlight

The City and the Stars

The Deep Range

and, best of all for me, and best of all of his books:

Childhood's End.

By the time I was eleven or twelve, I had made my way through these — and through Childhood's End more than once — as well as most of his short stories.

On the horizon even then, and gradually rising above it as I entered adolescence was Clarke's collaboration with Stanley Kubrick, which was released in the summer of 1968.

2001: A Space Odyssey remains, to my tastes (nor do I think I am alone) the finest science fiction film ever made, and one of the dozen or so finest films of any sort, it also served as a calling card introducing Clarke to an even larger audience than he already enjoyed. One grew accustomed to seeing him interviewed on television; he was a constant sage presence a year later during coverage of the first moon landing.

Other SF writers would make a large cultural impact — Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein, to name the other two of the "Big Three" as they are still known; Frank Herbert with the phenomenal success of Dune; Ray Bradbury for being, well, Ray Bradbury; Philip K. Dick posthumously and mostly through movies that misrepresent his books and vision.

But it was Arthur C. Clarke who broke through to the large mainstream media audience first, and remained through the rest of his long life a wise, bemused, funny, and insightful ambassador for SF, as well as for the enlightened use of technology to help rescue the world and its peoples from the situation(s) it found itself in and still does.

Weapons and weapons systems and warfare were definitely not among Arthur's visions enlightened applications of science, in the world or on the page. The best science fiction film of all time doesn't have a single gun in it. Nor do his novels contain the vast space battles that still afflict far too much print SF and virtually all filmed SF. Of his novels only Earthlight contains a space battle and, considering its author, you can be assured that it remains one of the best such battles ever set down.

After 2001 and Apollo, Clarke could have rested on his laurels — his achievement was already immense — and on the income produced by his speaking engagements, royalties, and the nonfiction that flowed steadily and always provocatively from his typewriter. But then he wouldn't have been Arthur C. Clarke.

Through the Seventies and beyond, more novels, ambitious ones, appeared:

Rendezvous With Rama (many people's choice for his second best novel)

Imperial Earth

The Fountains of Paradise (my choice for his second best novel)

The Songs of Distant Earth

Not to mention the other volumes in what became the Odyssey Quartet — 2010, 2061, 3001, as well as several smaller novels that lacked the ambition of his major works but carried the distinctive Clarke touch admirably. He remained a working writer through the last three decades of the Twentieth Century.

I leave aside the fact that over the last couple of decades of his life Clarke participated (that, I think, is the right word) in the creation of quite a few books with collaborators whose appearance did little to enhance his reputation. The best of these — his collaborations with Stephen Baxter — are honorable explorations of his ideas and themes, as was his final novel, The Last Theorem, written with Fred Pohl (that "with" is tricky: Fred did virtually all of the writing on this one, as I understand it). Theorem turned out to be not a particularly good example of either Clarke or Pohl, but it wasn't as bad as many thought. The collaborations with Baxter are, in their own way, excellent.

Of the other collaborations, licensings of his name, participation (there I go again) in television explorations of unexplained phenomena, and etc., not much to say. Most of these ventures have already faded or disappeared; most of Arthur's best books, fiction and nonfiction, continue to shine brightly.

Thinking about it, about him, about all he produced in fiction and nonfiction, all of the help he extended to his adopted Sri Lanka (and by extension to the rest of the emerging nations of our world), not to mention his genuine contribution to science and global communications — not for nothing are the orbits our comsats, as they used be called, known as Clarke Orbits — and all of the speeches and television appearances, I find myself actually amazed that he was only in his early 90s when he died. That much accomplishment in nine short decades? How is that possible?

Actually, it's pretty easy — if you're Arthur C. Clarke.

Which he was.

And still is and, I believe, will remain to be.

Happy Birthday, Arthur — nice to know that in so many ways you're still here.