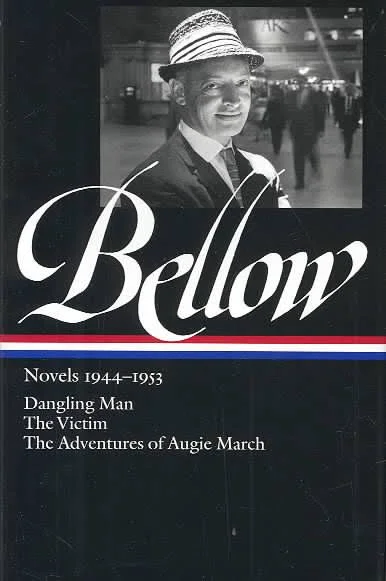

With the first of its (so far, but only so far, one hopes) Saul Bellow volumes, Novels 1944-1953, I was reminded by the volume title itself that while Bellow is (rightly) considered one of the half dozen or so key American postwar novelists, his career began while the war was still being waged.

That beginning, Dangling Man, is set in the United Sates (Chicago, of course) during the war. During, in fact, the narrator's wait for induction into the army: The arc of the novel is that wait; the novel is written in the form of diary entries.

It's an effective form both for the philosophical explorations Bellow pursued throughout his career — the narrator, Joseph, is well-read; books, their promise and their limitations (as well as Joseph's), inform many of the entries — and for propelling a narrative that isn't driven by plot. The book is essentially plotless (like life).

Casting the novel as a diary frees Bellow from building a cohesively plotted architecture of incidents and scenes (though there are plenty of each, some memorable) and enables the focus of the book to be Joseph's exploration of his identity, personally and philosophically.

The approach works well, though some entries demand some lenience of disbelief from the reader: though Joseph is not a novelist some entries run for several pages, complete with dialogue (in a party scene, dialogue from a fairly large number of characters) and novelistic descriptions.

Re-reading Dangling Man forty years after my first (and previously only) time with it offers certain pleasures of perspective. When I first read it, late in the Sixties, Bellow's most recent novel was Herzog (1964). At least two other major novels, Mr. Sammler's Planet (1970) and Humboldt's Gift (1975) and several close to major novels, not to mention nonfiction, stories and novellas and a Nobel Prize lay ahead.

That first reading of this first novel, though, came when the only other Bellow I knew was Herzog. Seize The Day (1957) and Henderson The Rain King (1959). The Adventures of Augie March (1953) and The Victim (1947) lay in my future, as they had in Bellow's when writing Dangling Man.

But even then and knowing only a few of his works I could see, nascent, many of Bellow's preoccupations, themes, and tones: Isolation, dialogues with the past and with one's self, troubles with women, engagement with and rejection of classical literature and philosophy, the costs (on many levels) of urban life, and others (though not Bellow's lively comic side: Dangling Man is, like its diarist/narrator, essentially humorless).

Looking at the book now, almost four years after Bellow's death, I find Dangling Man to be more compelling than I recalled, the diarist's wait — not quite anticipation — for induction and his emergence (sic) into a larger world giving a sense, wholly exclusive of the novel itself, of Bellow's own steady, day-by-day, page-by-page wait for his own emergence.

That emergence came with Augie March close to a decade after Dangling Man, and the third novel in the Library of America's first volume of Bellow. If I stick to my plan of reading may way through Bellow I will get to Augie...

Sometime. Rereading an author's work, all of it, in order of composition, is itself the work of a fair amount of a lifetime, and there are other writers I wish to approach the same way.

For now, though, I've begun Bellow, and recommend Dangling Man and its author to you, as well.